The digital era is a mixed bag. It’s handed us countless goodies but also opened doors to the dark alley of personal data theft. With recent hacks of DNA testing firms like 23andMe, what used to be a distant fear has become a grim reality. The thought of hackers rummaging through our DNA data is downright bone-chilling. So, how did we wind up here, and what spooks lie ahead?

CLICK TO GET KURT’S FREE CYBERGUY NEWSLETTER WITH SECURITY ALERTS, QUICK TIPS, TECH REVIEWS, AND EASY HOW-TO’S TO MAKE YOU SMARTER

A hacker claims to have leaked user’s private information from 23andMe. ( )

MORE: YOU ARE A HACKER TARGET WHETHER YOU KNOW IT OR NOT

What happened with the 23andMe leak

A hacker claims to have leaked and sold millions of users’ data from 23andMe. The hacker did not breach 23andMe’s systems but used credentials, that is, usernames and passwords, from other online platforms where users reused their passwords. The hacker also claimed to have data from celebrities, such as Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk, but this has not been verified by 23andMe.

The sky-high stakes of DNA data

The drama at 23andMe has shown a creepy twist in the hacking saga. It’s not just about swiping credit card numbers anymore; it’s about snagging the code that makes you, you. The information that has been exposed from the 23andMe incident includes genetic ancestry results, geographical location, full names, usernames, profile photos, sex, and date of birth. With cybercriminals now trading DNA data, it could open a can of worms we’ve never seen before – think identity theft on steroids or bio-engineered crimes from sci-fi horrors.

The corporate guard

Big names like 23andMe, DNA Diagnostics Center and MyHeritage are the keepers of our genetic secrets, and they have a huge load to carry. The toolkit to keep our genetic stuff safe needs to be rock-solid – strong encryption, regular security check-ups and user enlightenment on data safety. Clear rules on handling data and acting fast when things go south are key to winning back trust.

HOW YOUR CONNECTED HOME DEVICES COULD BE LEAVING YOU EXPOSED TO TROUBLE

Some companies holding our genetic information are 23andMe, DNA Diagnostics Center and MyHeritage. ( )

MORE: 7 EFFECTIVE WAYS TO MAKE YOUR LIFE MORE SECURE AND PRIVATE ONLINE

Now, in the digital Wild West, hackers are always on the lookout for precious data. Here’s a glimpse at what’s hot on the hacker’s wish list:

- Healthcare Data: This is like the crown in the hacker’s treasure chest. With medical records, insurance info, and prescription details, the dark deeds they can do are endless. From scoring drugs to fake insurance claims or selling your health secrets, it’s a mess waiting to happen.

- Personal Information: This is the hacker’s gold rush. Your name, address, phone number, email, birthdate, and Social Security number are all they need to stir up trouble. Breaking into your accounts, pretending to be you, or blackmail threats, the danger is real and relentless.

- Financial Data: This is where hackers hit the jackpot. With your credit card numbers, bank account details, they can play havoc with your finances. And if they sell this info to other bad guys, that’s just a downward spiral waiting to happen.

- Corporate Data: This is the top-tier loot. Trade secrets, customer lists, employee records, and financial reports are all up for grabs. With this info, hackers can cook up corporate disasters, from spying to reputation hits.

The digital frontier is stacked with risks, with hackers eyeing a big score at your expense. Both big-shot companies and everyday folks need to beef up their defenses to keep precious data away from digital pirates. With the right security gear, we can give hackers the boot and keep our digital kingdom safe.

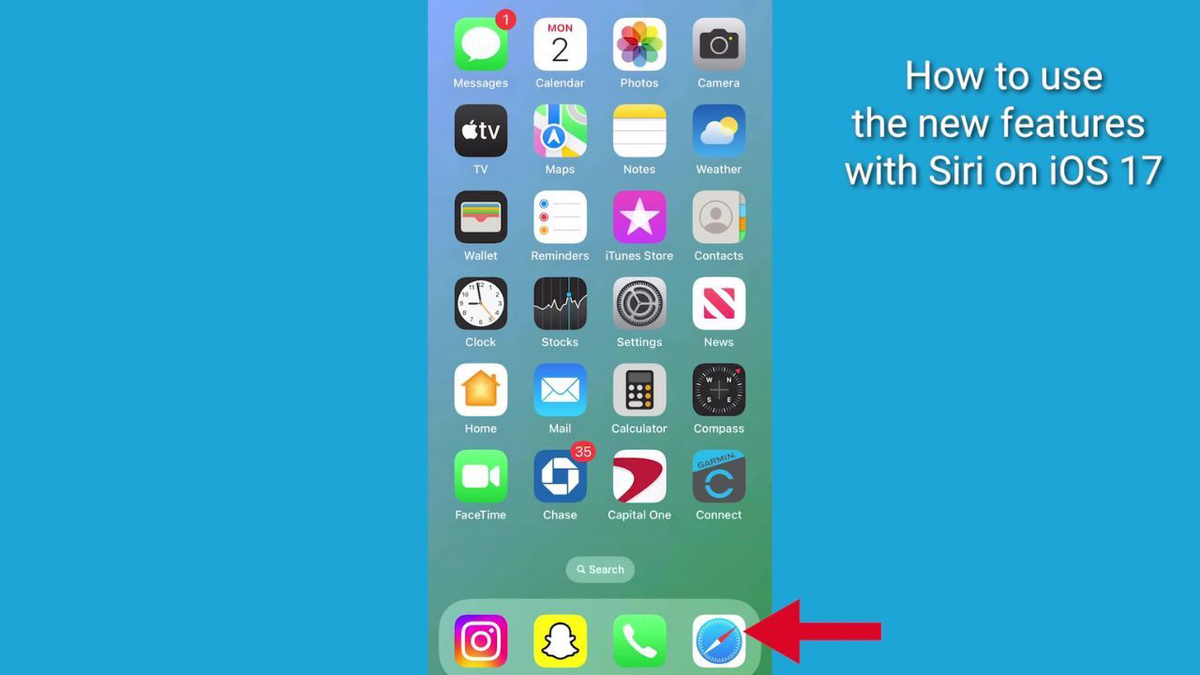

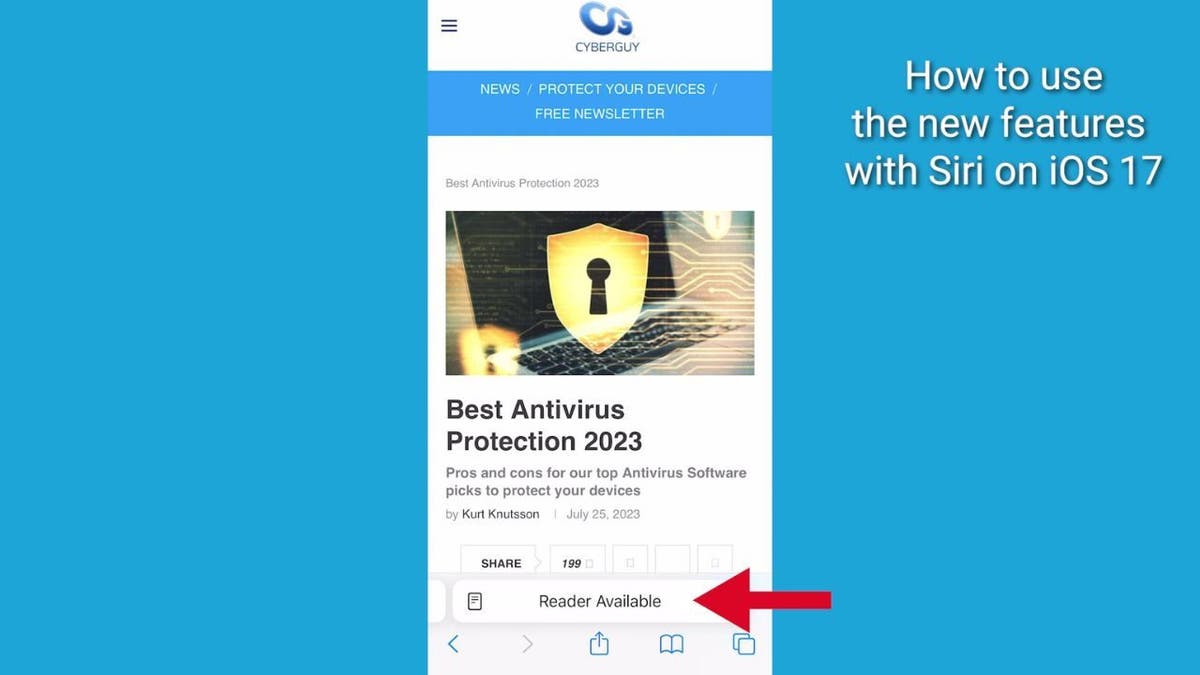

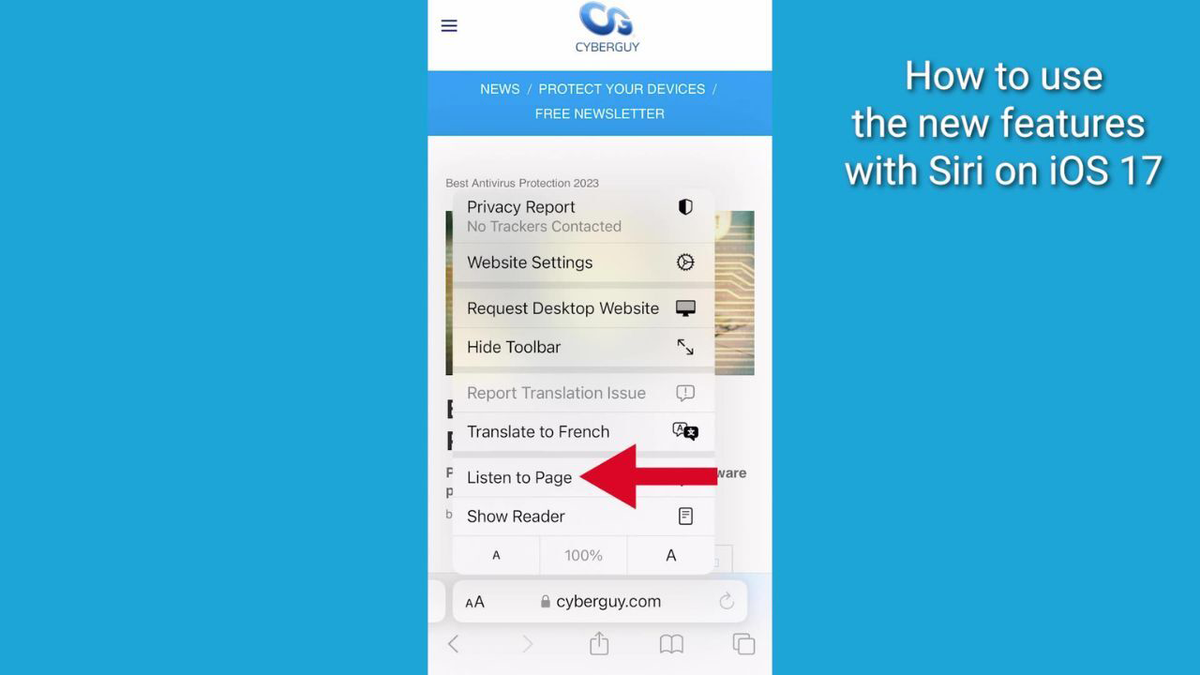

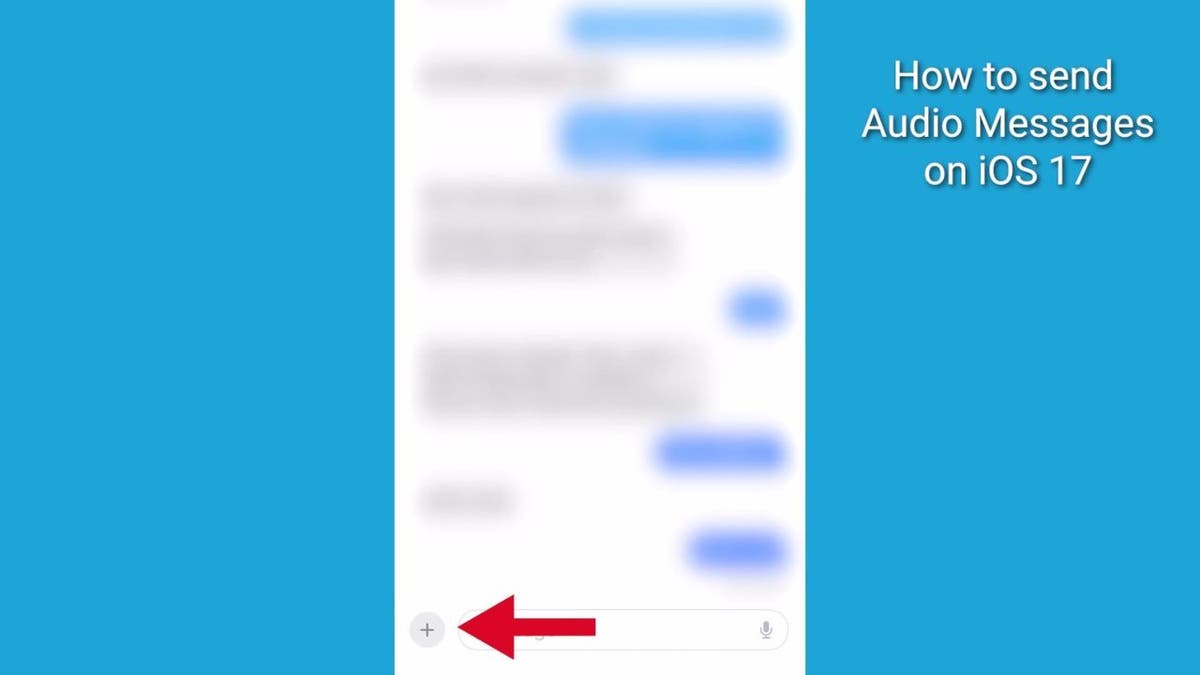

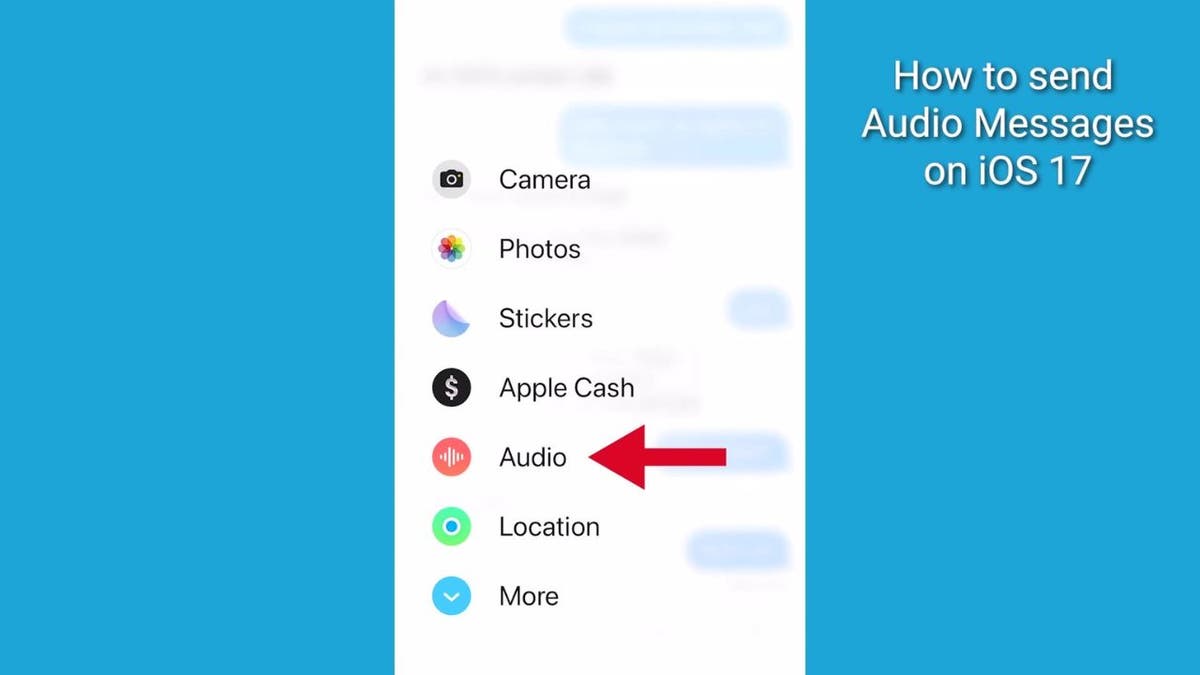

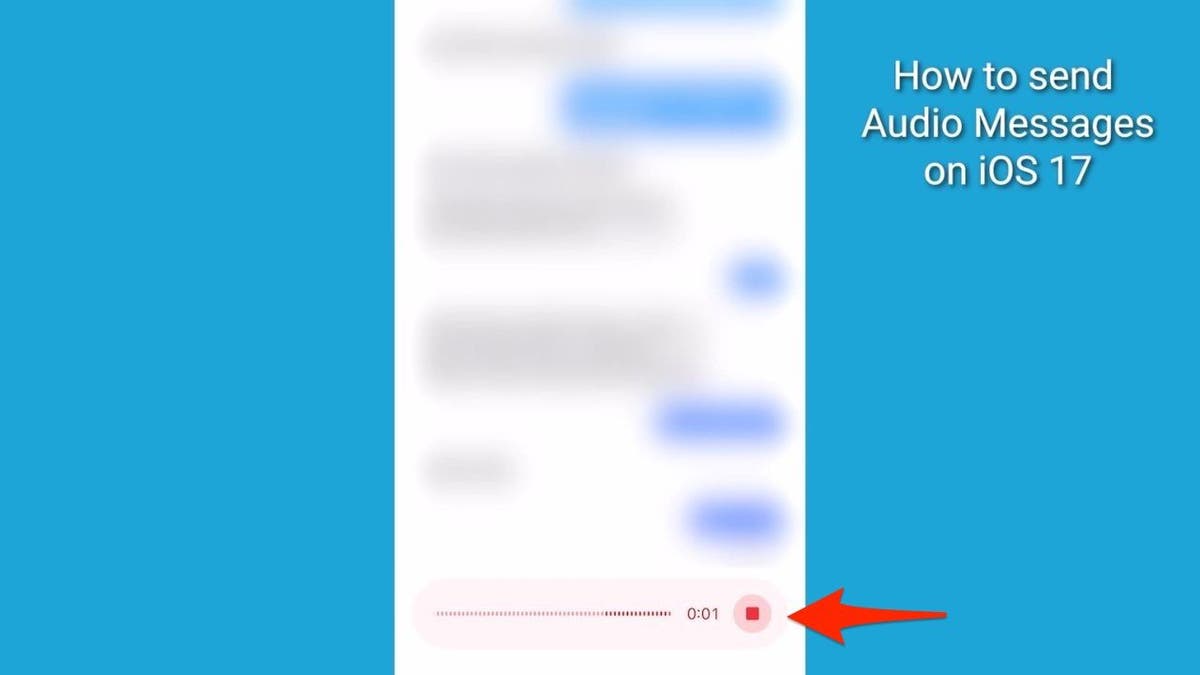

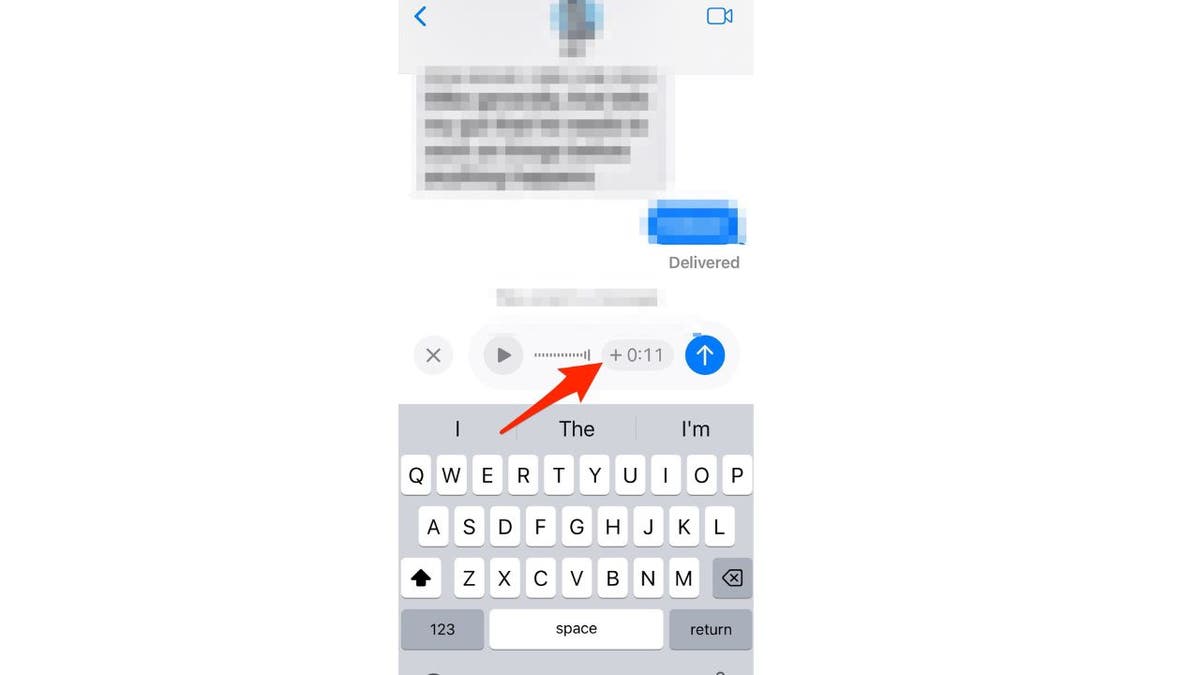

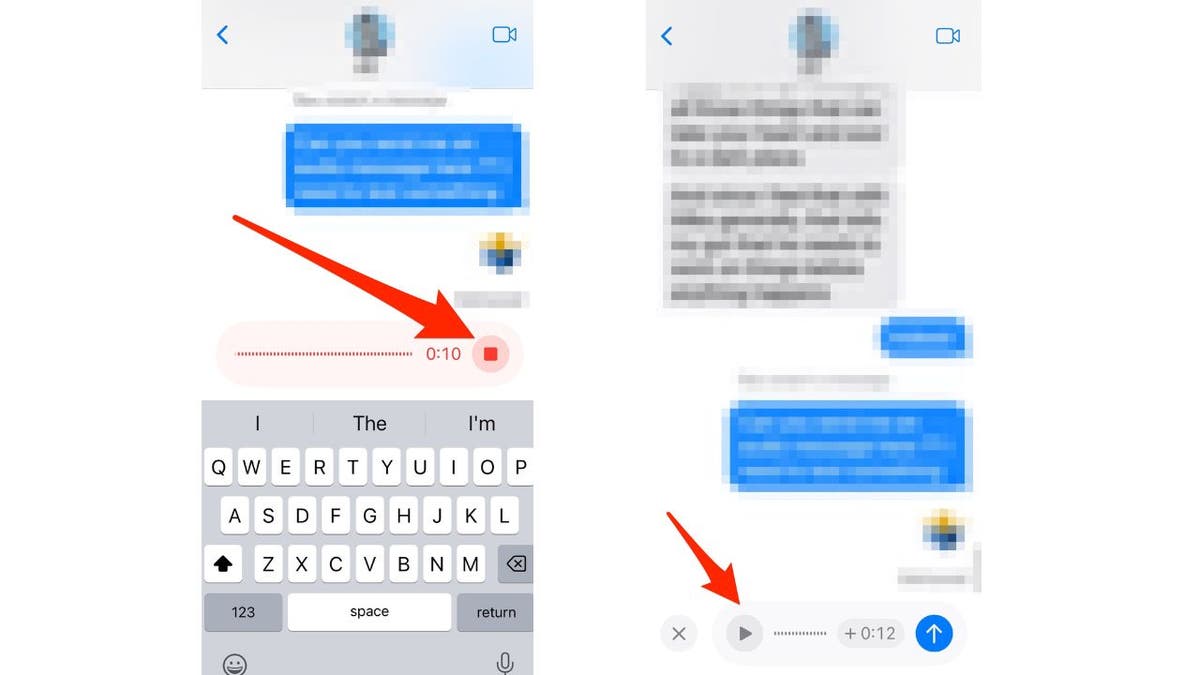

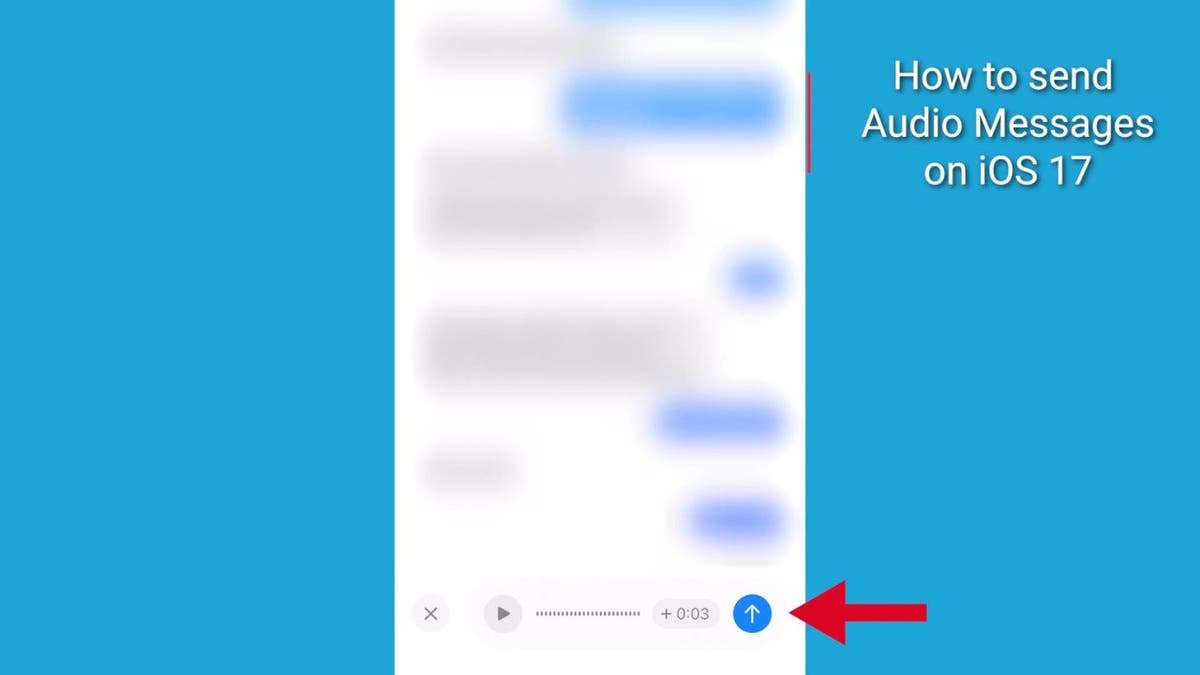

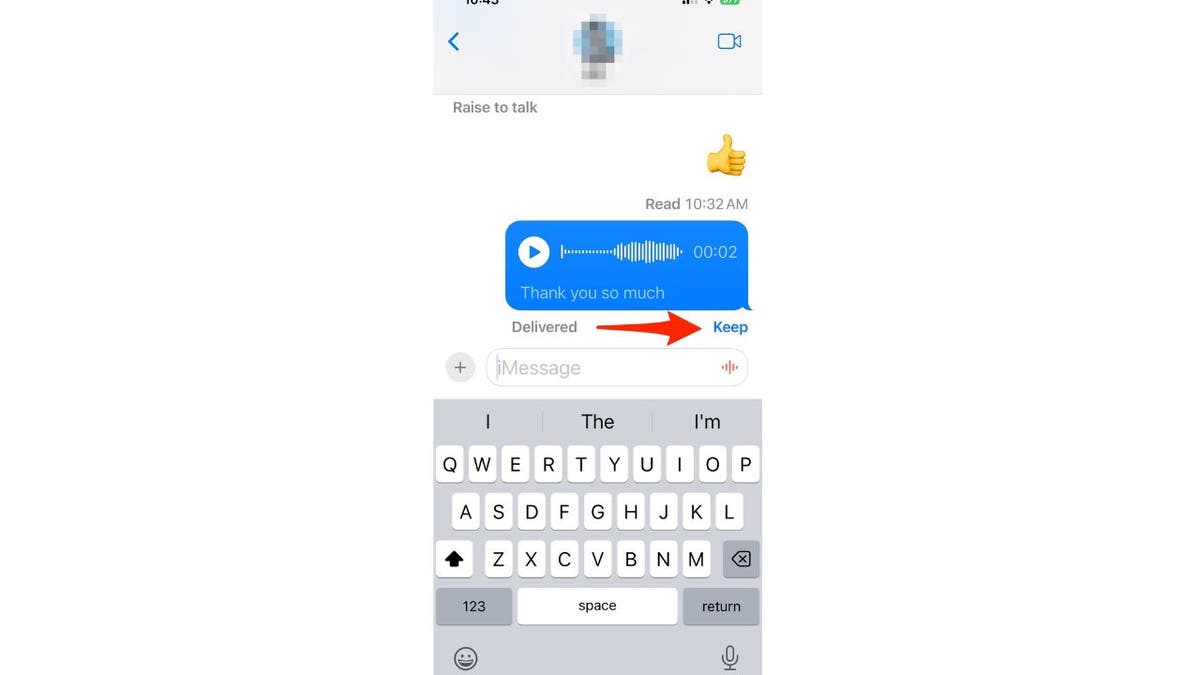

HOW TO USE THE NEW AUDIO MESSAGE FEATURES IN IOS 17

Hackers are on the prowl to steal your private information. ( )

GET MORE OF MY TECH TIPS & EASY VIDEO TUTORIALS WITH THE FREE CYBERGUY NEWSLETTER – CLICK HERE

How to protect your DNA data from potential misuse or theft

Read the privacy policies of the DNA testing companies before you share your genetic information with them. Some companies may share your data with third parties, such as researchers, law enforcement, or advertisers, without your explicit consent. You should know how your data will be used, stored and protected by the company you choose.

Opt out of any optional features that may compromise your privacy, such as public family trees, relative matching or health reports. These features may expose your personal or family information to other users or third parties. You should only use them if you are comfortable with the potential risks and benefits.

Encrypt your DNA data before you upload it to any online platform or database. Encryption is a method of transforming your data into a secret code that only you can unlock with a special key. This way, even if someone hacks into the platform or database, they won’t be able to read or use your data.

Delete your DNA data from the testing company’s website or database after you receive your results. Most companies allow you to request the deletion of your data and biological samples at any time. This will reduce the chances of your data being accessed by unauthorized parties in the future.

Be careful about who you share your DNA results with. Your genetic information may reveal sensitive information about yourself and your relatives, such as health conditions, ancestry or paternity. You should only share your results with people you trust and respect their privacy as well.

Use identity theft protection. If your data is stolen in an attack like the 23andMe leak, you will want to sign up for an identity theft protection service. Identity theft companies can monitor personal information like your home title, Social Security number, phone number, and email address, and alert you when it’s being sold on the dark web or being used to open an account in your name. They can also assist you in freezing your bank and credit card accounts to prevent further unauthorized use by criminals.

The great part of some identity theft companies is that they often include identity theft insurance of up to $1 million to cover losses and legal fees and a white glove fraud resolution team where a U.S.-based case manager helps you recover any losses.

See my tips and best picks on how to protect yourself from identity theft.

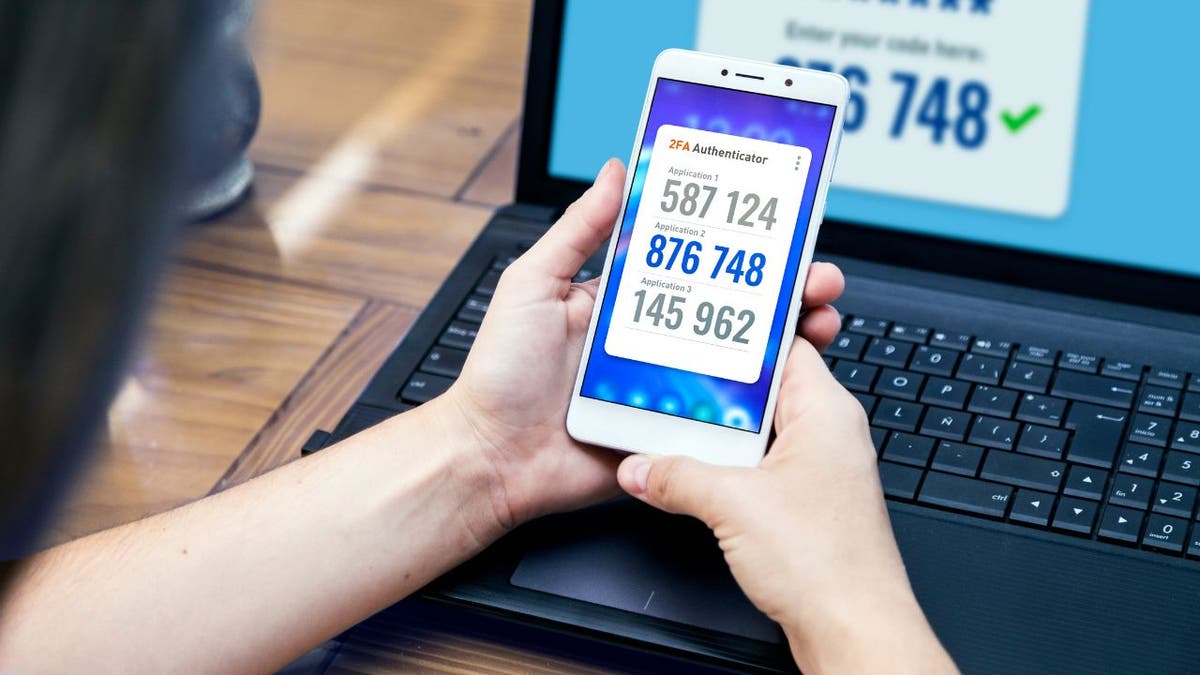

Use two-factor authentication (2FA): If a DNA testing company like 23andMe offers two-factor authentication, enable it. This adds an extra layer of security by requiring a second form of verification in addition to your password.

Create strong passwords for your DNA testing company accounts and the devices you use to log into those accounts. Also, avoid using the same password for multiple online accounts. That is how the 23andMe leak occurred. Consider using a password manager to securely store and generate complex passwords. It will help you to create unique and difficult-to-crack passwords that a hacker could never guess. Second, it also keeps track of all your passwords in one place and fills passwords in for you when you’re logging into an account so that you never have to remember them yourself. The fewer passwords you remember, the less likely you will be to reuse them for your accounts.

Get more details about my best expert-reviewed Password Managers of 2023.

What to do next if you become a victim of identity theft

Below are some next steps if you find you or your loved one is a victim of identity theft.

- If you can regain control of your accounts, change your passwords and inform the account provider.

- Look through bank statements and checking account transactions to see where outlier activity started.

- Use identity theft protection: Identity theft protection companies can monitor personal information like your home title, Social Security number, phone number, and email address and alert you if it is being sold on the dark web or being used to open an account. They can also assist you in freezing your bank and credit card accounts to prevent further unauthorized use by criminals. See my tips and best picks on how to protect yourself from identity theft.

- Report any breaches to state and local law enforcement and government agencies.

- Get the professional advice of a lawyer before speaking to law enforcement, especially when you are dealing with criminal identity theft. Also, seek legal advice if being a victim of criminal identity leaves you unable to secure employment or housing.

- Alert all three major credit bureaus and possibly place a fraud alert on your credit report.

- Run your own background check or request a copy of one if that is how you discovered your information has been used by a criminal.

If you are a victim of identity theft, the most important thing to do is to take immediate action to mitigate the damage and prevent further harm.

HOW TOM HANKS FAKE AI DENTAL PLAN VIDEO IS JUST THE BEGINNING OF BOGUS CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENTS

Kurt’s key takeaways

The recent hacks on DNA testing firms are a wake-up call, showing that our genetic data is now a hot target. I’m a customer of 23andMe from testing this concept for years, and now I am freaked out by the idea that someone potentially can infiltrate my deeply private DNA data.

It’s clear that both big companies and users need to step up precautions. So, while corporations beef up their systems, we should also do our bit by using strong passwords and turning on extra security features like multifactor authentication. It’s all about teaming up to keep out the digital bad guys.

How do you feel about the potential risks of sharing your DNA data with testing firms, knowing that you could be in danger of data theft? Let us know by writing us at Cyberguy.com/Contact.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Answers to the most asked CyberGuy questions:

Copyright 2023 CyberGuy.com. All rights reserved.

Kurt “CyberGuy” Knutsson is an award-winning tech journalist who has a deep love of technology, gear and gadgets that make life better with his contributions for Fox News & FOX Business beginning mornings on “FOX & Friends.” Got a tech question? Get Kurt’s CyberGuy Newsletter, share your voice, a story idea or comment at CyberGuy.com.